As activists call for an immediate investigation into his sibling's death, the brother of a teenage asylum seeker who committed himself while staying in a hotel run by the Home Office has spoken of the hopelessness and loneliness he feels contributed to his sibling's death.

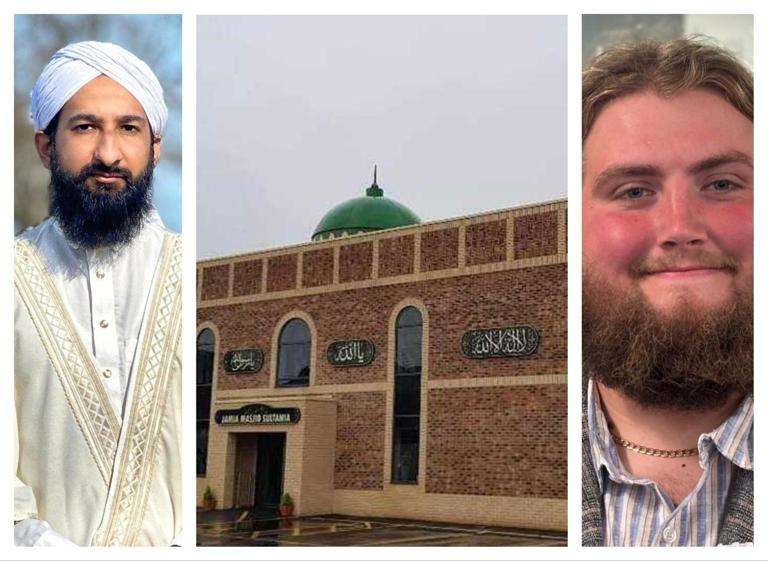

After fleeing Iran together and travelling across the Channel to the UK in a tiny boat many months previously, Ismael Maolanzadeh, then 19 years old, was discovered dead in a hotel room in Birmingham by his older brother Mustafa in December of last year.

A coroner last month found that the teenager had taken his own life following an argument with his long-distance girlfriend. But his older brother this week disputed the idea that a relationship row had spurred his sibling’s actions, saying instead that an absence of information about their fate in the asylum system had tipped his “joyful, happy” brother into a fatal depression.

The Kurdish brothers fled their native Iran in fear of arrest and possible capital punishment after taking part in protests against the Tehran regime. “We ran away from death and execution, but we didn’t know that he would die here,” Mustafa said.

Details of Ismael’s death have come to light after an investigation by i and Liberty Investigates established his identity from anonymised Home Office data which withheld his name and the location of his death.

The horse-loving teenager was one of 27 asylum claimants living in Home Office accommodation known to have taken their own lives in the past four years. Just two days after Ismael’s death, Leonard Farruku, a 27-year-old Albanian asylum seeker and musician, was found dead on the Bibby Stockholm barge having apparently taken is own life.

Lawyers and human rights groups have repeatedly raised concerns about the effects of long delays in the asylum system on the mental health of applicants as they wait months and even years for progress on their claims, with some facing the threat of deportation under the Government’s Rwanda scheme.

The Home Office underlined that it has measures in place to ensure that asylum seekers can access healthcare and support for vulnerable individuals. “We take the welfare of asylum seekers extremely seriously,” a spokesperson said.

Documents obtained under freedom of information rules show that Ismael’s case had been passed to the Home Office’s Third Country Unit (TCU), the immigration team responsible for deciding whether a migrant should be barred from applying to stay in the UK under new “inadmissibility” rules which automatically blocks claims for reasons such as entering the country illegally.

Ismael’s TCU status meant that he was at risk of inclusion in the new Rwanda scheme, although it appears his case had been paused at the time of his death and he was not formally informed of his status because of the legal and political wrangling over the policy at the time.

Lawyers, MPs and charities have questioned the investigation into Ismael’s death after an inquest hearing last month that was due to hear evidence from witnesses was cancelled and the formal procedure to decide how and why the teenager died was instead conducted using written submissions.

The verdict of suicide made no mention of the teenager’s asylum seeker status, prompting concern from one leading campaign group that, in the absence of a broader inquiry by the Home Office exploring safeguarding issues and the effect of the asylum system on the mental health of migrants, Ismael’s death had been “swept under the carpet”.

The decision to cancel the formal inquest hearing due on 29 April meant that Mustafa, who had become increasingly concerned at his sibling’s declining mental health after four months in which they had received no news on their asylum claims, was unable to testify about his brother’s well-being despite wishing to do so.

Mustafa, 23, this week told i and Liberty Investigates that his brother – a “joyful, happy boy” from whom he was “inseparable” – had become depressed since reaching Britain and struggled to cope in accommodation which felt more like a “prison”. He said: “We had so many plans together. We ran away from death and execution, but we didn’t know that he would die here… He was depressed most of the time.”

Mustafa said he was informed three weeks after his brother’s death that he had been listed as a witness to give evidence at an inquest hearing due to take place at the end of April. He was then “shocked” when he was told by hotel staff via the court shortly before the hearing that he would no longer be needed. No statement given personally by Mustafa appears in the evidence bundle compiled for the inquest. He said: “Since what happened, no-one [has] bothered to explain or to give me a clue about what’s going on.”

It has been established by i and Liberty Investigates that the only evidence submitted to the inquest as to whether Ismael’s mental wellbeing had been affected by his experience in the asylum system came in a written statement from a housing officer for Home Office contractor Serco. The worker at the hotel close to central Birmingham where Ismael and his brother had stayed since last August said her duties had included checking on the welfare of residents but that she had “not had any dealings” with Ismael prior to his death.

The employee said instead that there was “no suggestion that he suffered mental health issues or was feeling suicidal” after a computer system used to log information on asylum seekers at the hotel showed “no recorded incidents” relating to the teenager had been logged by staff. Serco pointed out that it is not responsible for the healthcare of residents and its employees are not directly employed as welfare support staff.

On the basis of the written submissions, Birmingham area coroner James Bennett found that the teenager had taken his life and that decision followed a “recent relationship breakdown” with his girlfriend in Iran. Mustafa has since disputed that this account, given to police on the day of his brother’s death, correctly reflects his brother’s state of mind, saying that while his sibling and his girlfriend sometimes argued, it was a “normal” part of their relationship.

Under rules introduced two years ago, coroners are now allowed to conduct inquests using written submissions for “straightforward and uncontentious” deaths if they do not believe a hearing is in the public interest. Like other parts of the justice system, the coroner’s service across Britain has faced growing backlogs of cases. Earlier this month, Judge Thomas Teague, the Chief Coroner for England and Wales, said “chronic underfunding” was a major factor in a 25 per cent year-on-year leap in the number of inquests taking more than a year to be resolved.

But legal experts and campaigners said they struggled to understand how the “very quick” handling of Ismael’s case could be reconciled with his status as a vulnerable young person who was effectively under the care of the British state.

Deborah Coles, executive director of Inquest, a charity specialising in state-linked deaths, said: “It is just too easy to sweep these deaths under the carpet with no meaningful engagement or no engagement at all from family and friends.

“There are fundamental questions to be asked of the Home Office about safeguarding and protection, particularly given the inherent vulnerabilities [of asylum seekers]. We should be calling for a broader investigation into these deaths.”

When asked about the conduct of the inquest into Ismael’s death, Louise Hunt, the senior coroner for Birmingham and Solihull said the proceedings had been concluded and pointed to guidance prohibiting coroners from commenting on cases. This guidance states: “Coroners are judicial office holders and like other judges are not permitted to comment outside a courtroom on any of their cases… or discuss any decision they have made.”

Five immigration lawyers and three Labour MPs have nonetheless joined a call from Inquest and the Refugee Council for an investigation into whether Ismael’s experience of the asylum system could have contributed to his death.

Laura Smith, co-legal director of the Joint Council for Welfare of Immigrants, said: “We see clients all the time who go months – sometimes years – without hearing any news from the Home Office. This leaves them unable to work, with no freedom, and cuts them off from communities by moving them around hotels and camps. The uncertainty and fear of detention and removal has a huge impact on people. Unfortunately, it is very common to see people’s mental health deteriorate further and further as they remain in the UK.”

Kim Johnson, Labour MP for Liverpool Riverside, who has campaigned on asylum issues, said she was concerned at a “fundamental lack of transparency and accountability” over Ismael’s death. She said the circumstances needed “thorough investigation”.

“One death of an asylum seeker in the care of our state is one death too many, it is a tragedy,” she said.

Despite the lack of detail in Home Office records, an in-depth investigation by i and Liberty Investigates was able to establish Ismael’s identity by obtaining emergency service data for sudden fatalities around the date of his death, which were subsequently confirmed with records held by the coroner’s service.

Mustafa described how he and his brother had departed last June from their home in Iran, where they worked as farmers, with dreams of becoming mechanics in Britain and escaping what he said was a constant threat of arrest and execution.

After travelling for two months across Europe, the pair crossed the Channel in a crude inflatable boat and were brought to Dover. They reached Birmingham in early August last year, eventually sharing a room in the hotel on the edge of the city centre, which houses some 320 asylum seekers.

Mustafa said Ismael had become increasingly disconsolate and despairing after going four months without any indication of their future status and growing unhappiness at their cramped living conditions, which he said were “like a prison”.

Speaking through a translator, Mustafa said: “You spend your time, 24 hours, between four walls and there’s nothing you can do. You don’t have money to go out. My brother was very, very active. He was always participating in the protests [in Iran]. He had a lot of energy. But once he got here, it’s like all these things had been taken away from him. He got depressed.”

Mustafa added that the pair had sometimes questioned their decision to come to Britain and whether they had a future in this country. He said: “We were saying, ‘look, we came all this way and we have risked our life’… Look where we are, we don’t belong anywhere.”

Zoe Bantleman, legal director of the Immigration Law Practitioners’ Association, said the Government’s inadmissibility policy had created “a large and ever-growing black hole of people left in permanent limbo”.

She said: “The vast majority are unremovable to countries with which they have no connection, but they are condemned to a life without hope of obtaining sanctuary and denied the opportunity to build a meaningful life.”

The elder brother, who said he is plagued by guilt at Ismael’s death, said he had gone for a haircut on 10 December last year and become increasingly concerned when his younger sibling had failed to answer phone calls. On his return to the hotel, he found Ismael unconscious and not breathing in their room. Attempts to administer CPR failed and Ismael was declared dead at the scene. No suicide note was found.

Mustafa added that he could not say with certainty whether his brother had been aware of the Rwanda scheme but said he believed the absence of information about his status had impacted his brother’s state of mind and his decision to take his life. He said: “If we at least had some information about what was going to happen to us… my brother might not have made that decision because we would have some hope.”

The older brother in particular disputed a description in a report of the death compiled by West Midlands Police which said he had told officers that Islmael had spoken to his girlfriend the day before his death and subsequently become “very upset and disengaged”. He said: “I was aware that sometimes they were having a fight. They were getting [back] together the next day. He was 19 years old. So I took it as something normal.”

A Home Office spokesperson said: “This was a tragic incident and our thoughts are with everyone affected. We take the welfare of asylum seekers extremely seriously. At every stage in the process, our approach is to ensure that all needs and vulnerabilities are identified and considered, including those related to mental health and trauma.”

_7.jpg)

_9.jpg)

.svg)