Weeks of escalating student protests have spiraled into Bangladesh's worst unrest in recent memory, with experts indicating that an inept government response has catalyzed a serious challenge to Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina's autocratic rule. What began as calls for the government to reform politicized civil service hiring rules has grown into massive demonstrations, fueled by a fierce police crackdown.

Tens of thousands of young, angry Bangladeshis are gathering on the streets each day, no longer just calling for policy changes but demanding an end to Hasina's tenure. "Down with the dictator," chanted protesters this week at several rallies across Dhaka, a sprawling megacity of 20 million, where incensed crowds set fire to several government buildings on Thursday.

Analysts say the crisis now facing Hasina and the ruling Awami League largely concerns the government's decision-making. "The protests are hugely significant... possibly the most serious challenge to the Awami League regime since it took office," Crisis Group Asia director Pierre Prakash told AFP. "Rather than try to address the protesters' grievances, the government's actions have made the situation worse," he added. "The country seems to be dangerously poised."

Meanwhile, the Hasina administration enforced an indefinite curfew and the army has been deployed.

The student campaign began with demands to end a quota system that reserves more than half of public sector jobs for specific groups. This scheme, established by Hasina's father, independence leader Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, reserves 30 percent of civil service posts for the children of veterans from the 1971 War of Liberation against Pakistan. Protesters argue this system rewards Awami League loyalists.

With Bangladesh struggling to provide adequate employment opportunities for its 170 million people, the scheme has become a pronounced source of resentment among young graduates facing an acute job crisis. Hasina further inflamed tensions by likening protesters to Bangladeshis who collaborated with Pakistan in 1971—a highly charged insult more than half a century after the conflict. "Mocking them was an insult to their dignity," Ali Riaz, a professor of politics at Illinois State University, told AFP. "It was also a message that they don't matter to a regime which is unaccountable."

Since taking office for a second time in 2009, rights groups and critics say Hasina and the Awami League have worked to dramatically curtail democracy in Bangladesh. Her government is accused of unjustly jailing her chief rival, passing draconian anti-press freedom laws, and committing numerous rights abuses, including the murder of opposition activists. This year, the Awami League won re-election in a vote without genuine opposition after a crackdown that saw hundreds from rival political parties arrested. Prakash noted that having not seen a genuinely competitive election in over 15 years, "discontented Bangladeshis have few options besides street protests to make their voices heard."

Hasina has weathered several dramatic crises during her tenure, including a brief army mutiny, the influx of more than 700,000 Rohingya refugees from neighboring Myanmar, and a spate of Islamist attacks. However, Tom Felix Joehnk, the long-term former Bangladesh correspondent for The Economist, said both the protests and the killings of students were "unprecedented." "Doing away with political competition in Bangladesh was always a bad idea," he told AFP. "At heart, this is a political crisis brought on by hubris and economic incompetence," he added. "Some 18 million young Bangladeshis are jobless. With democracy on hold for more than a decade, they are beginning to vote with their feet."

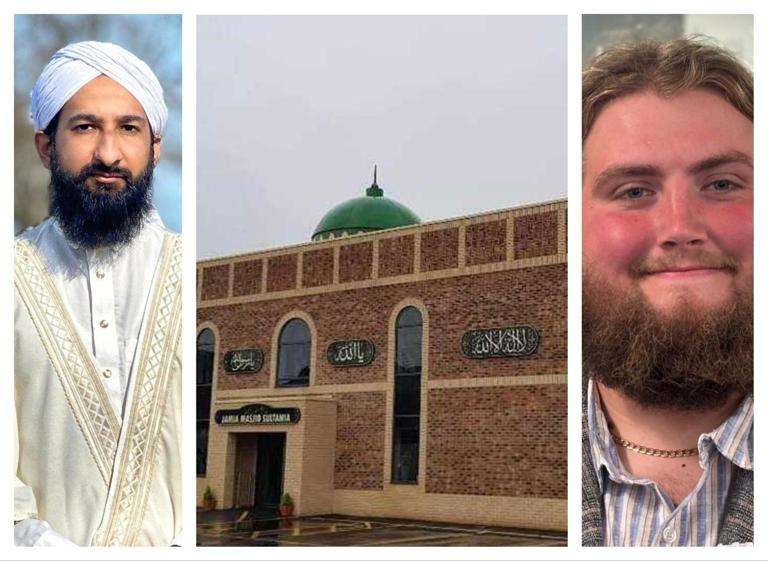

Author: Avik Sanwar Rahman, Executive Editor, The Bay Wave, USA

_7.jpg)

_9.jpg)

.svg)