Following the sacking of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, Bangladesh's army chief has pledged to support the country's interim government "no matter what" to help it complete key reforms and hold elections within the next 18 months.

General Waker-uz-Zaman and his troops stood aside in early August amid raging student-led protests against Hasina, sealing the fate of the veteran politician who resigned after 15 years in power and fled to neighbouring India.

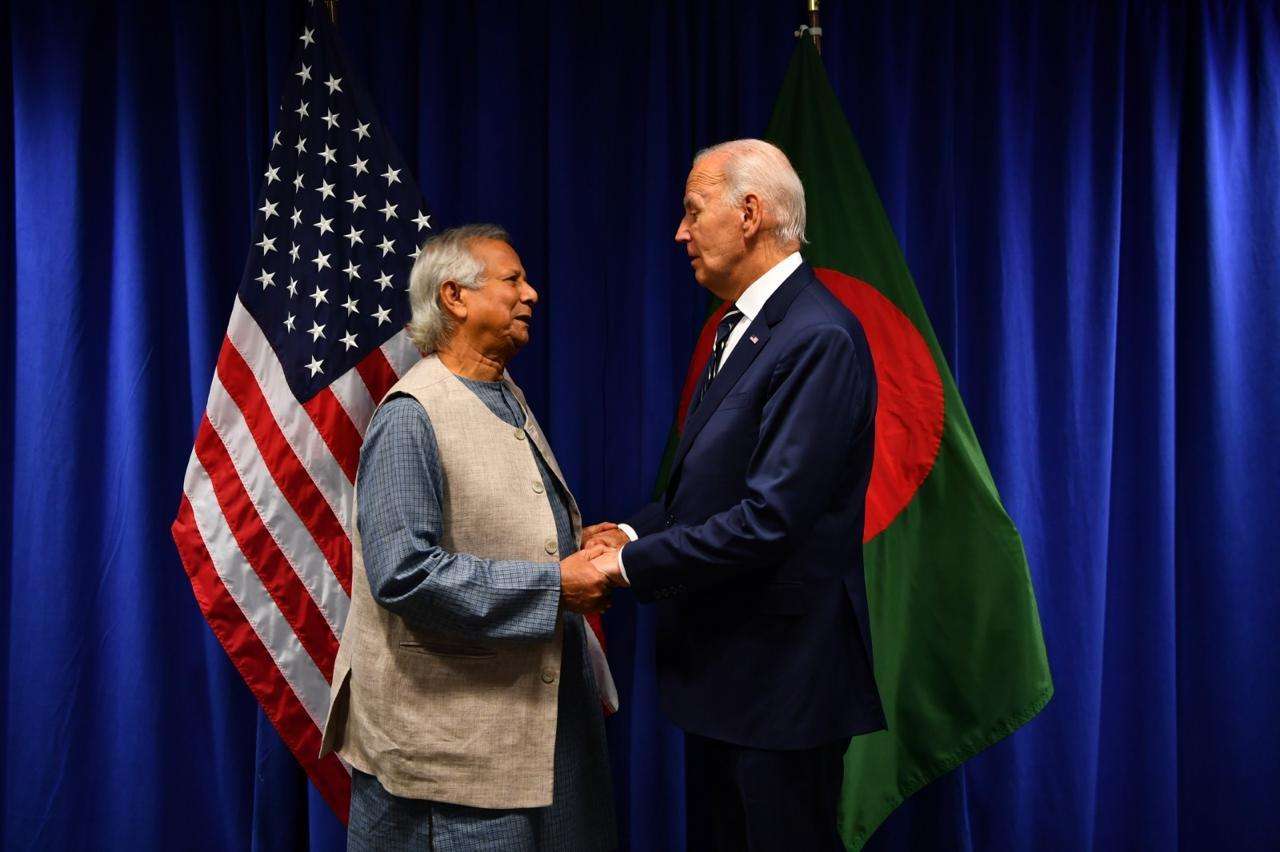

In a rare media interview, Zaman told Reuters at his office in the capital Dhaka on Monday that the interim administration led by Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus had his full support and outlined a pathway to rid the military of political influence.

“I will stand beside him. Come what may. So that he can accomplish his mission,” Zaman, bespectacled and dressed in military fatigues, said of Yunus.

The pioneer of the global microcredit movement, Yunus has promised to carry out essential reforms to the judiciary, police and financial institutions, paving the way to hold a free and fair election in the country of 170 million people.

Following the reforms, Zaman - who took over as the army chief only weeks before Hasina’s ouster - said a transition to democracy should be made between a year and a year-and-a-half, but underlined the need for patience.

“If you ask me, then I will say that should be the time frame by which we should enter into a democratic process,” he said.

Bangladesh’s main two political parties, Hasina’s Awami League and its bitter rival Bangladesh Nationalist Party, had both previously called for elections to be held within three months of the interim government taking office in August.

Yunus, the interim administration’s chief adviser, and the army chief meet every week and have “very good relations”, with the military supporting the government’s efforts to stabilise the country after a period of turmoil, said Zaman.

“I’m sure that if we work together, there is no reason why we should fail,” he said.

More than 1,000 people were killed in violent clashes that began as a movement against public sector job quotas in July but escalated into a wider anti-government uprising - the bloodiest period in the country’s independent history.

Calm has returned to the teeming streets of Dhaka, a densely packed metropolis that was at the heart of the rebellion, but some parts of the civil service are not yet properly functional after the dramatic fall of Hasina’s administration.

With much of Bangladesh’s police, numbering around 190,000 personnel, still in disarray, the army has stepped up to carry out law and order duties nationwide.

Punishments and reforms

Born out of erstwhile East Pakistan in 1971 after a bloody independence war, Bangladesh came under military rule in 1975, following the assassination of its first prime minister, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, Hasina’s father.

In 1990, the country’s military ruler Hossain Mohammad Ershad was toppled in a popular uprising, leading to the restoration of democracy.

The military again staged a coup in 2007, backing a caretaker government that ruled until Hasina took power two years later.

A career infantry officer who served through these periods of turmoil, Zaman said that the Bangladesh Army that he leads would not intervene politically.

“I will not do anything which is detrimental to my organisation,” he said, “I am a professional soldier. I would like to keep my army professional.”

In line with sweeping government reforms proposed since Hasina was shunted from power, the army, too, is looking into allegations of wrongdoing by its personnel and has already punished some soldiers, Zaman said, without providing further details.

“If there is any serving member who is found guilty, of course I will take action,” he said, adding that some military officials may have acted out of line while working at agencies directly controlled by the former prime minister or interior minister.

The interim government has formed a five-member commission, headed by a former high court judge, to investigate reports of up to 600 people who may have been forcibly “disappeared” by Bangladesh’s security forces since 2009.

In the longer-term, however, Zaman wanted to distance the political establishment from the army, which has more than 130,000 personnel and is a major contributor to United Nations peacekeeping missions.

“It can only happen if there is some balance of power between president and prime minister, where the armed forces can be placed directly under president,” he said.

Bangladesh’s armed forces currently come under the defence ministry, which is typically controlled by the prime minister, an arrangement that Zaman said a constitutional reform process under the interim government could potentially look to amend.

“The military as a whole must not be used for political purpose ever,” he said. “A soldier must not indulge in politics.”

_4.jpg)

.svg)

_5.jpg)