A proposed increase in the State Pension age to 70 is gaining momentum, but a deeper look into the health and mortality data of the UK's diverse communities reveals a stark and troubling reality, Daily Dazzling Dawn realized.

As the government faces escalating fiscal pressures, a rise in the State Pension age (SPA) has been put forward as a key solution. While a review into the SPA is scheduled for 2027, financial consultants and think tanks are pushing for swifter action. However, this national policy, framed as a uniform solution, threatens to disproportionately impact the health and quality of life for certain ethnic communities, particularly those of South Asian descent.

The Unequal Burden of Old Age

The idea of a retirement at 70 clashes with the reality of "healthy life expectancy" (HLE) — the number of years a person can expect to live in good health. For many, a later retirement age means an even shorter period of well-being before chronic illnesses take hold.

Updated data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) and other health bodies highlights significant disparities. A study on life expectancy in Scotland found that while British Bangladeshi women had the highest life expectancy of any group at 87.3 years, the picture changes when considering overall health. Research from 2001 revealed that Bangladeshi men had the lowest "disability-free life expectancy" (DFLE) at 54.3 years, while Pakistani women had a DFLE of 55.1 years. These figures suggest that while members of these communities may live long lives, they are more likely to spend a significant portion of their later years in poor health, a period that would be directly impacted by a later retirement age.

Mortality Rates Tell a Grim Story

Beyond life expectancy, mortality data paints a more complex picture. While some studies have shown that many ethnic minority groups have lower overall mortality rates than the White British population, this "healthy migrant effect" is often reversed for specific diseases and for those born in the UK.

According to a report from The Health Foundation, Black and mixed/multiple ethnicity groups had some of the highest mortality rates among men born in the UK. For UK-born women, the highest mortality rates were found in those of Bangladeshi and mixed/multiple ethnicity backgrounds. This is often linked to the higher prevalence of specific health conditions. For example, people of South Asian descent face significantly higher risks of cardiovascular disease and diabetes, while Black groups have a higher risk of prostate cancer.

Furthermore, a 2023 report from the National Child Mortality Database showed that Black infants were nearly three times more likely to die than White infants, and the mortality rate for Black infants had risen sharply. This, combined with the higher rates of specific diseases in the adult population, illustrates a systemic health inequality that a later retirement age would exacerbate.

A Future of Work, Not Rest

For many, retirement is not just a financial break but a cultural and social milestone. A policy that pushes this back risks creating a future where a significant portion of the workforce, particularly in communities already facing health disparities, is forced to work until their bodies give out.

The government's commitment to the triple lock—which guarantees the State Pension rises by the highest of inflation, earnings, or 2.5%—is a major factor in the escalating costs. Critics, like economist Ben Ramanauskas, argue this mechanism is unsustainable and should be replaced. However, this debate about fiscal prudence often overshadows the human cost. The current SPA is scheduled to rise to 67 between 2026 and 2028, with a rise to 68 planned for 2044-2046. The upcoming review in 2027 is a critical juncture where a decision to accelerate this timeline could have profound consequences for those who can least afford it.

For many, a job is a core part of their identity. But when a job means little to no time for rest, it becomes a burden rather than a source of dignity. The current policy debate risks creating a future where certain communities are sentenced to a life of work with no true retirement.

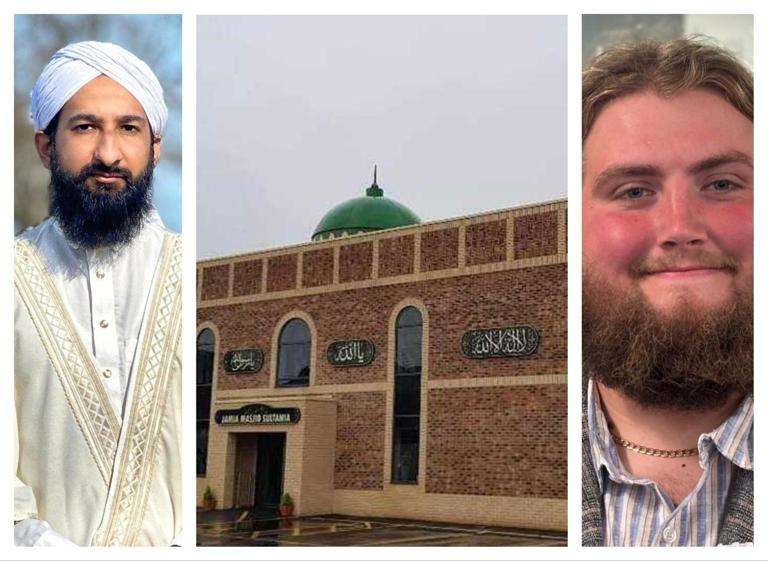

Many British Bangladeshi's told to Daily Dazzling Dawn,from our community's perspective, this isn't just a financial issue; it's a matter of dignity and justice. Many of our elders have spent their lives in physically demanding jobs, building lives for themselves and their families. When we look at the data on healthy life expectancy and the higher rates of conditions like diabetes and heart disease, a retirement age of 70 feels less like an opportunity and more like an impossible target. We are being asked to work until we are physically broken, with no guarantee of a peaceful retirement. The system, in its current form, does not seem to recognize the unique health challenges and lived experiences of our communities. It feels like a sentence to a life of labor without the promise of rest.

_8.jpg)

_7.jpg)

.svg)