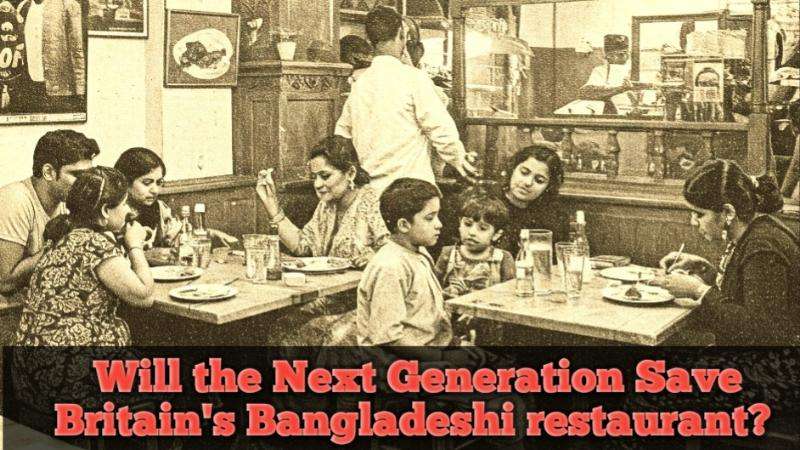

The fragrant allure of chicken tikka masala and the comforting sizzle of sweet and sour chicken have been culinary cornerstones of British life for decades. But the family-run Bangladeshi and Chinese restaurants that brought these flavors to our tables are facing an unprecedented crisis, raising the question: is this the last generation?

These establishments, often born from the hard work and sacrifice of immigrant families, are grappling with soaring costs, changing consumer habits, and a reluctance among younger generations to take up the demanding mantle.

"The restaurant was like a second home," recalls Dipna Anand, whose family's Brilliant Restaurant, a Punjabi culinary institution, has served London for nearly half a century. Like her, Amy Poon, whose parents' Michelin-starred Chinese restaurant, Poon's of Covent Garden, shaped London's dining scene, grew up amidst the clatter of kitchens and the hum of dining rooms.

However, the realities of the restaurant business—long hours, grueling work, and slim profit margins—have deterred many of their peers. "The industry wasn't glamorous or well regarded," says Poon, "so it's small wonder that a Chinese restaurant kid would want to pursue another avenue."

The "immigrant bargain," as sociologists call it, saw many children of these restaurateurs pursuing professional careers, fulfilling their parents' dreams but leaving the family business behind. "Unlike our parents' generation, who built their businesses through sheer hard work and long hours, many younger generations have seen firsthand the sacrifices involved," explains Anand.

Adding to the challenge are the economic pressures. Rising ingredient, energy, and labor costs, coupled with the hefty commission fees charged by delivery apps like Deliveroo and Uber Eats (often 25-35%), are squeezing already thin profit margins. This forces many restaurants to raise prices, potentially driving away customers.

Moreover, the perception of these restaurants is often skewed. Many Bangladeshi-run establishments are incorrectly labeled as "Indian," obscuring their unique culinary heritage. This mislabeling, combined with some restaurants' struggles to maintain consistent quality amidst rising costs, has created a perception of high prices and comparatively low quality.

"Customer habits have changed, too," Anand notes. "People expect quicker service, more convenience, and competitive pricing, which can be difficult to balance while maintaining quality."

Despite these challenges, there is hope. Some are innovating, adapting traditional flavors to modern formats. Poon, for example, has launched pop-ups and a sauce range, while Anand is transitioning to a gastropub, blending her family's culinary legacy with a contemporary dining experience.

New-wave concepts like Three Uncles and Rice Guys are also demonstrating that traditional Asian cuisine can thrive in modern, fast-casual settings. "These are brilliant, thriving, delicious examples of the Chinese takeaway, brought into the next generation," says Poon.

While the future of family-run British Bangladeshi, British South Asian, British Indian, British Pakistani and Chinese restaurants remains uncertain, their impact on British culinary culture is undeniable. These were the places that introduced us to new flavors, celebrated our milestones, and comforted us on quiet nights. Whether they choose to inherit, reinvent, or walk away, their stories—and their food—will continue to shape our palates and our memories.

_4.jpg)

.svg)