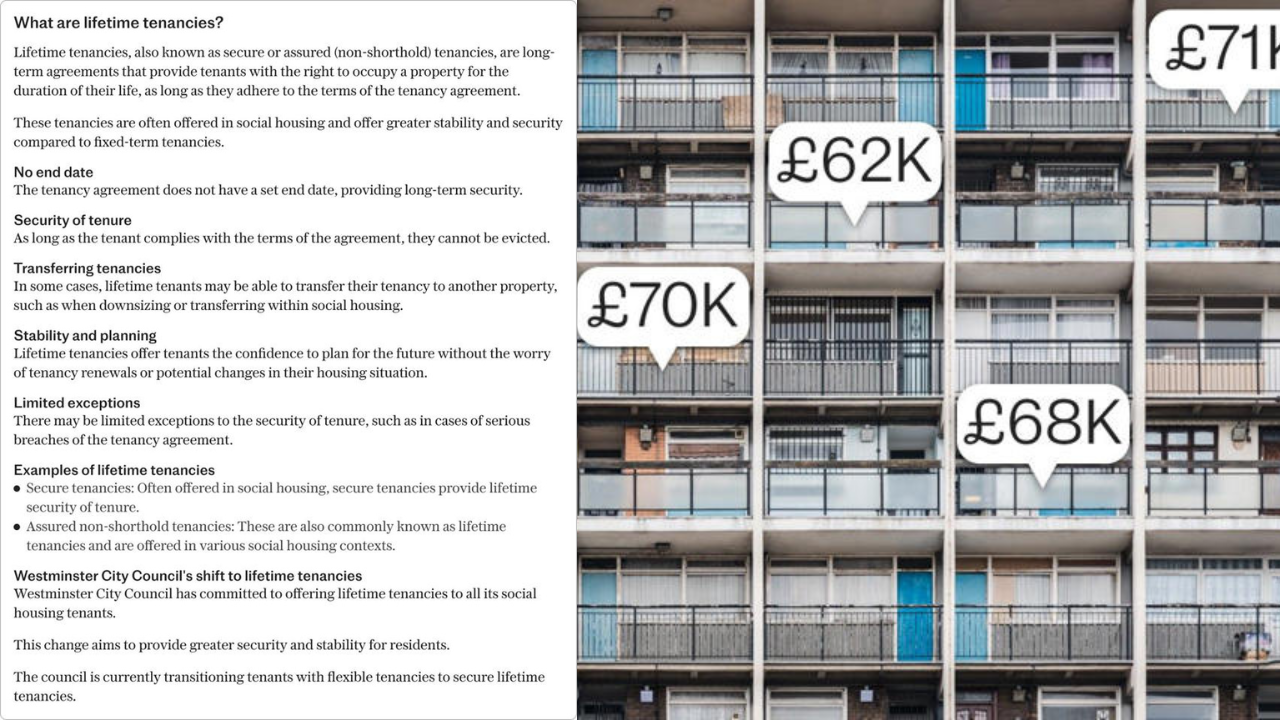

The landscape of social housing in the UK is under scrutiny as recent figures reveal a notable proportion of higher-income households residing in taxpayer-subsidised homes, even as the national waiting list for such properties continues to grow. Analysis of official data indicates that approximately 128,000 households in social housing, representing 3.2% of the four million social housing households in England between 2023 and 2024, earned at least £71,344 annually. This figure places them among the country's top earners. An additional 315,000 households were found to earn at least £46,176 a year.

These figures contrast with the most recent government data, which places the average household income in the UK at £55,000 per year. The proportion of social housing households in the highest income bracket has seen an increase from 2.7% between 2015 and 2016 to the current 3.2%.

This comes at a time when the demand for social housing is intensifying. As of March 2024, 1.3 million households were awaiting a social housing placement, marking a 3% increase within a year and reaching its highest point since 2014.

Critics argue that the continued occupancy of lower-cost social housing by higher earners exacerbates the challenges faced by those in greater need. Kevin Hollinrake, the shadow housing secretary, stated, "With over a million households on the social housing waiting list, it’s impossible to justify high earners remaining in taxpayer-subsidised homes. Government subsidies should be focused on those in greatest need. Social housing exists as a safety net, and resources should be targeted at the poorest to ensure the system remains fair and effective.”

Social housing offers significantly lower rental costs compared to the private sector. Official figures from 2023 to 2024 show that social housing tenants in England paid, on average, 55% of the weekly median market rate. In London, this disparity is even more pronounced, with weekly social housing rents at 40% of those in the private rental sector. For a household earning £71,344 a year, an average social housing rent in England would account for approximately 11% of their take-home pay, compared to nearly double that, 20%, for a private rental property.

The vast majority of social housing households remain in the lowest income categories, with just over 47% earning as little as £76 a week, and 27.6% earning at least £360 a week. While income details are typically provided upon application for social housing, tenants are generally not disqualified from their tenancy if their income increases later.

The current system primarily operates on secure tenancies, also known as lifetime placements, which are the default offering by almost all local authorities. Attempts to alter this system, including a 2012 move by a coalition government to give local authorities discretion to not offer lifetime tenancies (which saw low uptake), and a 2015 Conservative proposal to scrap them entirely (later shelved), have not been implemented. Similarly, "Pay to Stay" rules, proposed in 2016 by former chancellor George Osborne to require higher earners to pay more for social housing, were also never enforced. As of March 2024, lifetime tenancies constituted 89.9% of new council lettings.

A government spokesman commented, “It is up to individual councils to make housing decisions based on people’s needs – but higher earning tenants make up just 3% of the overall social housing population. Our focus is on taking action to deliver our stretching target of 1.5 million homes, including the biggest boost to affordable and social housing in a generation – backed by £39bn – to tackle the housing crisis we’ve inherited head on and give more families a safe, secure home.”

A spokesman for the Local Government Association emphasised the need for increased housing supply: “We are facing a housing crisis, and councils need to be empowered to build more affordable, good quality homes quickly and at scale. Individual council have policies on how to allocate social housing. These are in line with priority need and relevant legislation, and response to changes in circumstance are for individual authorities to outline in their housing policies.”

The ongoing debate highlights the complexities of addressing the UK's housing challenges, balancing the immediate needs of those on waiting lists with the existing framework of social housing allocation and the broader aim of increasing housing availability.

Source- Telegraph

.svg)