[caption id="attachment_2295" align="alignleft" width="824"]

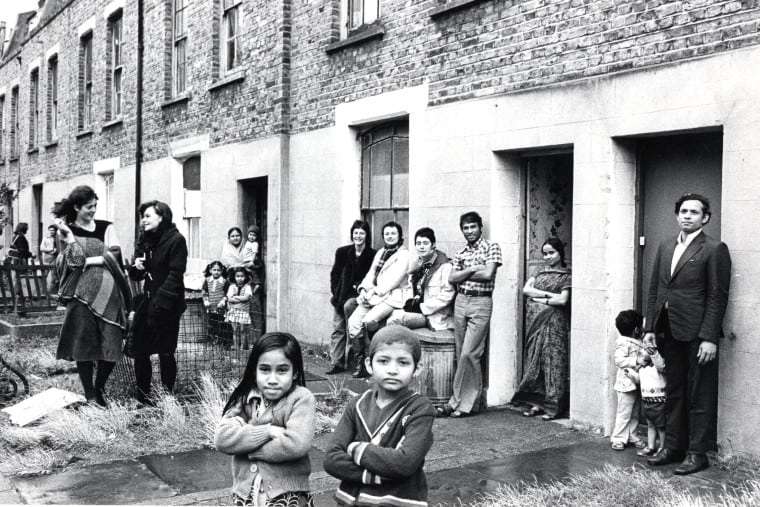

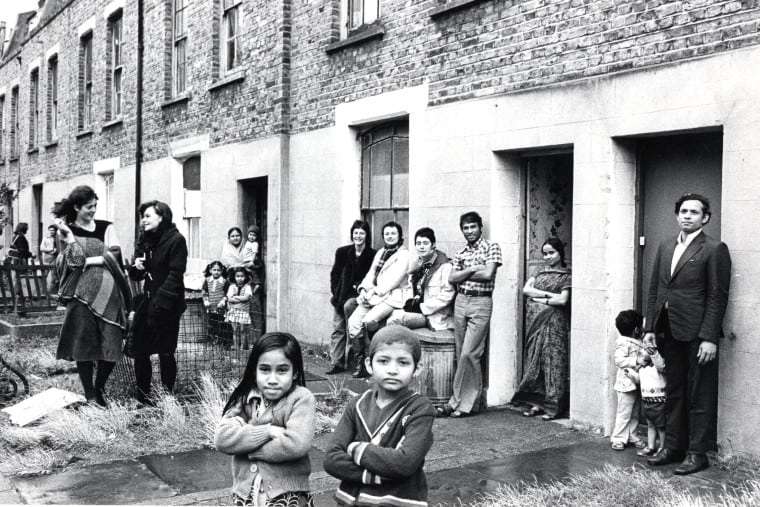

A housing co-op in Stepney Green (Picture: Angela Phillips)

A housing co-op in Stepney Green (Picture: Angela Phillips)[/caption]

Struggle and resistance have allowed Bangladeshi migrants to build a home in London's East End. Today, some celebrate the Bengali migrants as a success story of liberal integration. Others try to leverage their achievements to sell Bangladeshi street food restaurants that have become famous.

But neither side remembers the land grab movement of the 1970s that allowed these migrants to settle in Tower Hamlets, on the outskirts of the City of London. They also do not want to discuss the fact that people were forced to organize self-defense against a wave of racist violence led by the fascist National Front. Author Shabna Begum's realization that her parents and other first-generation Bangladeshis in the East End would soon pass away prompted her to collect their stories.

She has carefully combined their stories into a new book, From Sylhet to Spitalfields, a book full of protest. It ultimately tells how squatters took over the council and local authority and were eventually recognized by law as tenants.

Among many others, she talks about Abdul Kadir, who came to Britain in 1957. He lived in the East End for decades as he sought to attract connections from Bangladesh. For a time, her family of five lived in a room that didn't even have a proper bathroom. Public housing officials refused to hear his case.

Ultimately, Kadir decided to take matters into his own hands. He saw an empty flat in a nearby council estate and told his wife Sufia that they should take it, knowing that many desperate Bangladeshis were doing the same.

“So, I went and I broke the door, and once inside I called out to someone I knew. I got him to stay there. You needed to have a mattress or two to (legally) claim it, so all the way from my flat I got a mattress, I carried it all the way over.”

But within minutes of the family’s arrival, dozens of racist youth gathered outside to attack them.

“We were pelted with stones from all directions,” says Kadir. “They broke all the glass, the front and the side windows, all of them. The police came, not to see who had broken the windows, but to ask why we were there and to get us out.”

Kadir told police they would have to go to court if they wanted to deport him. And he also stood up to a racist housing officer who was trying to evict them.

Eventually, there were so many squatters in the area that housing officials gave up trying to stop them.

Begum emphasized the role of women in the movement. They fight with bailiffs and officials during the day when their partners are at work, and it is the women who have to protect their children from daily abuse.

Recalling her altercations with police and housing officers who came to her door, squatter Sufia says, “What were they saying, who knows? But you can tell from their tone. I would just say, ‘Come back another day, I don’t understand’.

“Of course, I did understand, they were telling me to get out, but I just kept saying, ‘I don’t understand! (laughs).”

Squatters often take over buildings abandoned by city authorities in an attempt to eliminate slums. And they keep their own housing listings, prioritizing housing for families and the elderly.

This type of requisition required organization and in 1976 the Bengali Housing Action Group was formed, under the influence of the far-left group, the Race Today collective.

Before long, hundreds of families abandoned by the state were receiving independent help. Begum's story of resistance is especially valuable because of the way mainstream politics in the past and present have tended to characterize migrants.

Politicians invariably see them as a “problem” that needs to be managed and “outsiders” that cannot lay claim to the same rights as white British people.

That’s why council housing in Tower Hamlets and beyond was allocated on an assumed “belonging” to an area, rather than need.

This was a policy deliberately designed to exclude immigrants, but also to create the illusion among white workers that those in power valued their supposed kinship .

From Sylhet to Spitalfields, the film challenges the common misconception that Asians, and Asian women in particular, are too soft to stand up for themselves. At that time, it was common to hear even good union members describe Asians as fodder for the bosses, used to lower wages.

They insist that Bangladeshis and others like them could never organize.

This stereotype still exists. Across Asia, women today are seen as being controlled by fathers, husbands, and brothers and in need of “liberation by the West.”

As Begum shows, many Bangladeshi women in the East End refused to play this role. And the fight for housing shows that migrants can organize in the most imaginative ways and employ the most militant methods.

Far from being a weakness of the labor movement, they can also be its strength. Begum is not afraid to accept the racism of those at the top and the way they spread poison to those at the bottom. It explores how the speeches of Conservative MP Enoch Powell and future Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher fanned the flames of racism and how both legitimized widespread “Paki bashing”.

The term became widely used in the early 1970s, after the press began reporting violence against Eastern Bangladeshis. For its part, The Observer noted: “Any Asian who recklessly walks the streets alone at night is a fool. »

It is therefore not surprising that this protest against racist violence is another important part of the book. Jalal Rajonuddin is one of many young Bangladeshis who want to fight back.

He told Begum, “I remember the period when people used to go out only in groups so that if they came under attack they could try to save or defend themselves. “That’s how life was. The community was under siege.”

But local politicians were keen to suggest that Bangladeshis had brought the violence upon themselves because they had “failed to fit in” and integrate.

Husnara, a mother of four, took inspiration from the Bangladesh War of Liberation against Pakistan in 1971.

She told Begum, “We all had to fight, even us (women)… we had so much trouble, but we even enjoyed that fight (laughs) if I’m honest.

“Life was sad and happy. In Bangladesh there was one war, here there was another war—and we won this place, we claimed it.”

Some in the squatter’s movement sought to defend the community from racist gangs by roaming the area in groups, ready to fight them. But another strand of resistance was also forming—the mass demonstration.

Starting in 1976 Bangladeshi street protests became popular and drew in wider forces from the left, especially after the racist murder of Altab Ali in May 1978.

Some were sceptical about radical groups, and even hostile, but far from all. Rafique Ullah arrived in Britain as a young boy in 1972 and was at that time a member of the Bangladeshi Youth Front that helped build the Altab Ali protest.

He told Begum, “We never had mobiles… But more than 10,000 people came from Birmingham, Manchester, Sheffield and Leeds.

“Those were the industrial towns, our people used to be there, they came—by coach loads.

We had Socialist Workers Party, Anti Nazi League support us too. They came attending our demonstration. Without their support we would not be successful.”

The book goes on to note the way community organising was to pull many of the best activists into broader political life—and not a few into narrow self-interest. It also shows that at the height of the struggle Bangladeshi migrants were able to challenge institutional prejudice and racism on the street.

It was those battles that made it possible for Bangladeshis to live and work across Tower Hamlets.

However, Begum also shows how divisions on questions of politics and strategy within this group of migrants returned to the fore once the immediacy of battle had passed.

A housing co-op in Stepney Green (Picture: Angela Phillips)[/caption]

Struggle and resistance have allowed Bangladeshi migrants to build a home in London's East End. Today, some celebrate the Bengali migrants as a success story of liberal integration. Others try to leverage their achievements to sell Bangladeshi street food restaurants that have become famous.

But neither side remembers the land grab movement of the 1970s that allowed these migrants to settle in Tower Hamlets, on the outskirts of the City of London. They also do not want to discuss the fact that people were forced to organize self-defense against a wave of racist violence led by the fascist National Front. Author Shabna Begum's realization that her parents and other first-generation Bangladeshis in the East End would soon pass away prompted her to collect their stories.

She has carefully combined their stories into a new book, From Sylhet to Spitalfields, a book full of protest. It ultimately tells how squatters took over the council and local authority and were eventually recognized by law as tenants.

Among many others, she talks about Abdul Kadir, who came to Britain in 1957. He lived in the East End for decades as he sought to attract connections from Bangladesh. For a time, her family of five lived in a room that didn't even have a proper bathroom. Public housing officials refused to hear his case.

Ultimately, Kadir decided to take matters into his own hands. He saw an empty flat in a nearby council estate and told his wife Sufia that they should take it, knowing that many desperate Bangladeshis were doing the same.

“So, I went and I broke the door, and once inside I called out to someone I knew. I got him to stay there. You needed to have a mattress or two to (legally) claim it, so all the way from my flat I got a mattress, I carried it all the way over.”

But within minutes of the family’s arrival, dozens of racist youth gathered outside to attack them.

“We were pelted with stones from all directions,” says Kadir. “They broke all the glass, the front and the side windows, all of them. The police came, not to see who had broken the windows, but to ask why we were there and to get us out.”

Kadir told police they would have to go to court if they wanted to deport him. And he also stood up to a racist housing officer who was trying to evict them.

Eventually, there were so many squatters in the area that housing officials gave up trying to stop them.

Begum emphasized the role of women in the movement. They fight with bailiffs and officials during the day when their partners are at work, and it is the women who have to protect their children from daily abuse.

Recalling her altercations with police and housing officers who came to her door, squatter Sufia says, “What were they saying, who knows? But you can tell from their tone. I would just say, ‘Come back another day, I don’t understand’.

“Of course, I did understand, they were telling me to get out, but I just kept saying, ‘I don’t understand! (laughs).”

Squatters often take over buildings abandoned by city authorities in an attempt to eliminate slums. And they keep their own housing listings, prioritizing housing for families and the elderly.

This type of requisition required organization and in 1976 the Bengali Housing Action Group was formed, under the influence of the far-left group, the Race Today collective.

Before long, hundreds of families abandoned by the state were receiving independent help. Begum's story of resistance is especially valuable because of the way mainstream politics in the past and present have tended to characterize migrants.

Politicians invariably see them as a “problem” that needs to be managed and “outsiders” that cannot lay claim to the same rights as white British people.

That’s why council housing in Tower Hamlets and beyond was allocated on an assumed “belonging” to an area, rather than need.

This was a policy deliberately designed to exclude immigrants, but also to create the illusion among white workers that those in power valued their supposed kinship .

From Sylhet to Spitalfields, the film challenges the common misconception that Asians, and Asian women in particular, are too soft to stand up for themselves. At that time, it was common to hear even good union members describe Asians as fodder for the bosses, used to lower wages.

They insist that Bangladeshis and others like them could never organize.

This stereotype still exists. Across Asia, women today are seen as being controlled by fathers, husbands, and brothers and in need of “liberation by the West.”

As Begum shows, many Bangladeshi women in the East End refused to play this role. And the fight for housing shows that migrants can organize in the most imaginative ways and employ the most militant methods.

Far from being a weakness of the labor movement, they can also be its strength. Begum is not afraid to accept the racism of those at the top and the way they spread poison to those at the bottom. It explores how the speeches of Conservative MP Enoch Powell and future Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher fanned the flames of racism and how both legitimized widespread “Paki bashing”.

The term became widely used in the early 1970s, after the press began reporting violence against Eastern Bangladeshis. For its part, The Observer noted: “Any Asian who recklessly walks the streets alone at night is a fool. »

It is therefore not surprising that this protest against racist violence is another important part of the book. Jalal Rajonuddin is one of many young Bangladeshis who want to fight back.

He told Begum, “I remember the period when people used to go out only in groups so that if they came under attack they could try to save or defend themselves. “That’s how life was. The community was under siege.”

But local politicians were keen to suggest that Bangladeshis had brought the violence upon themselves because they had “failed to fit in” and integrate.

Husnara, a mother of four, took inspiration from the Bangladesh War of Liberation against Pakistan in 1971.

She told Begum, “We all had to fight, even us (women)… we had so much trouble, but we even enjoyed that fight (laughs) if I’m honest.

“Life was sad and happy. In Bangladesh there was one war, here there was another war—and we won this place, we claimed it.”

Some in the squatter’s movement sought to defend the community from racist gangs by roaming the area in groups, ready to fight them. But another strand of resistance was also forming—the mass demonstration.

Starting in 1976 Bangladeshi street protests became popular and drew in wider forces from the left, especially after the racist murder of Altab Ali in May 1978.

Some were sceptical about radical groups, and even hostile, but far from all. Rafique Ullah arrived in Britain as a young boy in 1972 and was at that time a member of the Bangladeshi Youth Front that helped build the Altab Ali protest.

He told Begum, “We never had mobiles… But more than 10,000 people came from Birmingham, Manchester, Sheffield and Leeds.

“Those were the industrial towns, our people used to be there, they came—by coach loads.

We had Socialist Workers Party, Anti Nazi League support us too. They came attending our demonstration. Without their support we would not be successful.”

The book goes on to note the way community organising was to pull many of the best activists into broader political life—and not a few into narrow self-interest. It also shows that at the height of the struggle Bangladeshi migrants were able to challenge institutional prejudice and racism on the street.

It was those battles that made it possible for Bangladeshis to live and work across Tower Hamlets.

However, Begum also shows how divisions on questions of politics and strategy within this group of migrants returned to the fore once the immediacy of battle had passed.

A housing co-op in Stepney Green (Picture: Angela Phillips)[/caption]

Struggle and resistance have allowed Bangladeshi migrants to build a home in London's East End. Today, some celebrate the Bengali migrants as a success story of liberal integration. Others try to leverage their achievements to sell Bangladeshi street food restaurants that have become famous.

But neither side remembers the land grab movement of the 1970s that allowed these migrants to settle in Tower Hamlets, on the outskirts of the City of London. They also do not want to discuss the fact that people were forced to organize self-defense against a wave of racist violence led by the fascist National Front. Author Shabna Begum's realization that her parents and other first-generation Bangladeshis in the East End would soon pass away prompted her to collect their stories.

She has carefully combined their stories into a new book, From Sylhet to Spitalfields, a book full of protest. It ultimately tells how squatters took over the council and local authority and were eventually recognized by law as tenants.

Among many others, she talks about Abdul Kadir, who came to Britain in 1957. He lived in the East End for decades as he sought to attract connections from Bangladesh. For a time, her family of five lived in a room that didn't even have a proper bathroom. Public housing officials refused to hear his case.

Ultimately, Kadir decided to take matters into his own hands. He saw an empty flat in a nearby council estate and told his wife Sufia that they should take it, knowing that many desperate Bangladeshis were doing the same.

“So, I went and I broke the door, and once inside I called out to someone I knew. I got him to stay there. You needed to have a mattress or two to (legally) claim it, so all the way from my flat I got a mattress, I carried it all the way over.”

But within minutes of the family’s arrival, dozens of racist youth gathered outside to attack them.

“We were pelted with stones from all directions,” says Kadir. “They broke all the glass, the front and the side windows, all of them. The police came, not to see who had broken the windows, but to ask why we were there and to get us out.”

Kadir told police they would have to go to court if they wanted to deport him. And he also stood up to a racist housing officer who was trying to evict them.

Eventually, there were so many squatters in the area that housing officials gave up trying to stop them.

Begum emphasized the role of women in the movement. They fight with bailiffs and officials during the day when their partners are at work, and it is the women who have to protect their children from daily abuse.

Recalling her altercations with police and housing officers who came to her door, squatter Sufia says, “What were they saying, who knows? But you can tell from their tone. I would just say, ‘Come back another day, I don’t understand’.

“Of course, I did understand, they were telling me to get out, but I just kept saying, ‘I don’t understand! (laughs).”

Squatters often take over buildings abandoned by city authorities in an attempt to eliminate slums. And they keep their own housing listings, prioritizing housing for families and the elderly.

This type of requisition required organization and in 1976 the Bengali Housing Action Group was formed, under the influence of the far-left group, the Race Today collective.

Before long, hundreds of families abandoned by the state were receiving independent help. Begum's story of resistance is especially valuable because of the way mainstream politics in the past and present have tended to characterize migrants.

Politicians invariably see them as a “problem” that needs to be managed and “outsiders” that cannot lay claim to the same rights as white British people.

That’s why council housing in Tower Hamlets and beyond was allocated on an assumed “belonging” to an area, rather than need.

This was a policy deliberately designed to exclude immigrants, but also to create the illusion among white workers that those in power valued their supposed kinship .

From Sylhet to Spitalfields, the film challenges the common misconception that Asians, and Asian women in particular, are too soft to stand up for themselves. At that time, it was common to hear even good union members describe Asians as fodder for the bosses, used to lower wages.

They insist that Bangladeshis and others like them could never organize.

This stereotype still exists. Across Asia, women today are seen as being controlled by fathers, husbands, and brothers and in need of “liberation by the West.”

As Begum shows, many Bangladeshi women in the East End refused to play this role. And the fight for housing shows that migrants can organize in the most imaginative ways and employ the most militant methods.

Far from being a weakness of the labor movement, they can also be its strength. Begum is not afraid to accept the racism of those at the top and the way they spread poison to those at the bottom. It explores how the speeches of Conservative MP Enoch Powell and future Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher fanned the flames of racism and how both legitimized widespread “Paki bashing”.

The term became widely used in the early 1970s, after the press began reporting violence against Eastern Bangladeshis. For its part, The Observer noted: “Any Asian who recklessly walks the streets alone at night is a fool. »

It is therefore not surprising that this protest against racist violence is another important part of the book. Jalal Rajonuddin is one of many young Bangladeshis who want to fight back.

He told Begum, “I remember the period when people used to go out only in groups so that if they came under attack they could try to save or defend themselves. “That’s how life was. The community was under siege.”

But local politicians were keen to suggest that Bangladeshis had brought the violence upon themselves because they had “failed to fit in” and integrate.

Husnara, a mother of four, took inspiration from the Bangladesh War of Liberation against Pakistan in 1971.

She told Begum, “We all had to fight, even us (women)… we had so much trouble, but we even enjoyed that fight (laughs) if I’m honest.

“Life was sad and happy. In Bangladesh there was one war, here there was another war—and we won this place, we claimed it.”

Some in the squatter’s movement sought to defend the community from racist gangs by roaming the area in groups, ready to fight them. But another strand of resistance was also forming—the mass demonstration.

Starting in 1976 Bangladeshi street protests became popular and drew in wider forces from the left, especially after the racist murder of Altab Ali in May 1978.

Some were sceptical about radical groups, and even hostile, but far from all. Rafique Ullah arrived in Britain as a young boy in 1972 and was at that time a member of the Bangladeshi Youth Front that helped build the Altab Ali protest.

He told Begum, “We never had mobiles… But more than 10,000 people came from Birmingham, Manchester, Sheffield and Leeds.

“Those were the industrial towns, our people used to be there, they came—by coach loads.

We had Socialist Workers Party, Anti Nazi League support us too. They came attending our demonstration. Without their support we would not be successful.”

The book goes on to note the way community organising was to pull many of the best activists into broader political life—and not a few into narrow self-interest. It also shows that at the height of the struggle Bangladeshi migrants were able to challenge institutional prejudice and racism on the street.

It was those battles that made it possible for Bangladeshis to live and work across Tower Hamlets.

However, Begum also shows how divisions on questions of politics and strategy within this group of migrants returned to the fore once the immediacy of battle had passed.

_2.jpg)

_1.jpg)

.svg)