Donald Trump is set to encounter strong opposition from Jordan’s King Abdullah during their meeting at the White House today, marking their first discussion since the US president suggested relocating Gaza’s population to Jordan.

As a key ally of the United States, Jordan has been carefully balancing its military and diplomatic relations with Washington while maintaining strong public support for the Palestinian cause.

These existing tensions, already strained by the ongoing Gaza War, are now being pushed to the limit by Trump’s proposed plans for Gaza’s future.

Expanding on his earlier call for Gazans to be moved to Jordan and Egypt, Trump told a Fox News anchor that they would not have the right to return home—a proposal that, if implemented, would violate international law.

On Monday, he warned that US aid to Jordan and Egypt could be withheld if they refused to accept Palestinian refugees.

Among the staunchest opponents of relocating Gazans to Jordan are those who have already been displaced from Gaza in the past.

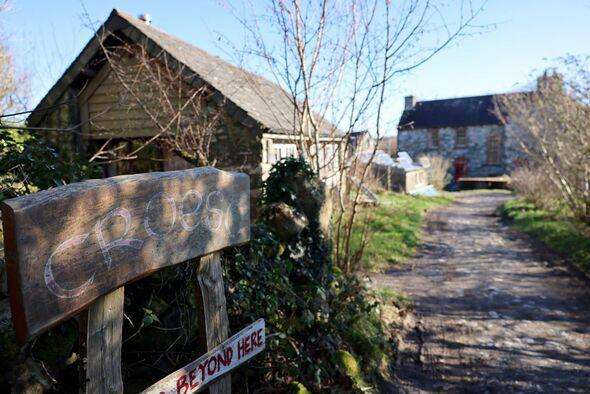

Around 45,000 people reside in the Gaza Camp near Jerash, a northern Jordanian town. It is one of several Palestinian refugee camps in the country.

In the camp, narrow shopfronts are shaded by sheets of corrugated iron, while children navigate the crowded streets on donkeys, weaving between market stalls.

Every family in the camp traces its origins to Gaza—to places like Jabalia, Rafah, and Beit Hanoun. Many fled after the 1967 Arab-Israeli war, expecting temporary refuge. Decades later, they remain in Jordan, unable to return.

"Donald Trump is an arrogant narcissist," says 60-year-old Maher Azazi. "He thinks like a medieval tradesman."

Maher was just a toddler when he left Jabalia. Some of his family remain there, now searching through the ruins of their home for the bodies of 18 missing relatives.

Despite the destruction, Mr. Azazi insists that Gazans today have learned from the past, and most would "rather jump into the sea than leave."

Those who once saw displacement as a temporary escape now believe it only serves Israel’s far-right nationalists in their effort to claim Palestinian land.

"We Gazans have experienced this before," says Yousef, who was born in the camp. "They told us it was temporary, that we would return home. But the right to return is non-negotiable."

Another man adds, "When our ancestors left, they had no weapons to fight back, like Hamas does now. But today’s generation knows what happened to our elders, and we won’t let history repeat itself. Now, there is resistance."

Jordan has long been a refuge, not just for Palestinians but for others fleeing regional conflicts.

Iraqis arrived in the early 2000s, escaping war. A decade later, Syrians followed, prompting Jordan’s king to warn that his country was at a "boiling point."

Many native Jordanians blame successive waves of refugees for worsening unemployment and poverty. A food bank near a mosque in central Amman says it distributes 1,000 meals daily.

Waiting for work outside the mosque, we met Imad Abdallah and his friend Hassan – both day labourers who have not worked in months.

"The situation in Jordan used to be great, but when there was the war in Iraq, things got worse, when there was the war in Syria, it got worse, now there's a war in Gaza, it's got a lot worse," Hassan said. "Any war that happens near us, we become worse off, because we're a country that helps and takes people in."

Imad was blunter, worried about feeding his four children.

"The foreigners come, and take our jobs," he told me. "Now I'm four months without a job. I have no money, no food. If Gazans come, we will die."

But Jordan is also under pressure from its key military ally. Trump has already suspended to it US aid worth more than $1.5 billion a year. And many here are braced for a growing confrontation between the new US president and their own political leaders, who are pushing back.

Jawad Anani, a former deputy prime minister with close ties to the Jordanian government, says King Abdullah will deliver a firm message to Donald Trump at the White House on Tuesday:

"We see any effort by Israel or others to force people out of their homes in Gaza and the West Bank as a criminal act. But any attempt to push those people into Jordan would be considered an act of war."

Even if Gazans were willing to relocate temporarily as part of a broader Middle East plan, he argued, the fundamental issue was a lack of trust.

"There is no confidence," he stated. "As long as Netanyahu and his government are involved, no one can trust any promises that are made. Period."

Trump’s insistence on pushing his vision for Gaza risks forcing a key US ally into a difficult decision.

Last Friday, thousands of Jordanians took to the streets in protest against his proposal.

Jordan hosts US military bases and millions of refugees, while its security cooperation is essential for Israel, which is concerned about smuggling routes into the occupied West Bank.

Any threats to Jordan’s stability pose risks for its allies as well. If Jordan’s greatest strength is its stability, then the potential for unrest is both its greatest weapon and its strongest form of leverage.

.svg)