The United Kingdom is sitting on a potential economic boon: an estimated £31.1 billion in "lost" pensions, spread across 3.3 million forgotten accounts, averaging nearly £9,500 per individual. This staggering sum, largely accumulated through auto-enrolment and increased job mobility, represents not just a personal financial loss for savers but also a significant missed opportunity for the UK economy.

The Lost Billions: A Growing Problem

According to the Pensions Policy Institute, the volume of dormant pension funds continues to rise. Many individuals have simply forgotten about these pots, or mistakenly believe they are contributing solely to the state pension. While some providers like Aviva are making efforts to reunite savers with their funds (Aviva alone has traced nearly 36,000 pensions worth £426 million), many pension institutions appear to prioritise collecting fees over proactive tracing.

The complexity of tracing these funds is undeniable. Frequent job changes, company takeovers, and changes in address make it difficult to piece together an individual's pension journey. While the DWP offers a letter forwarding service for £5 per enquiry, the current system is cumbersome for providers, and the incentive to pay to potentially lose funds to another provider is low. Furthermore, the DWP's form only allows for seven enquiries per submission, a significant hurdle when dealing with millions of lost pensions.

Government Intervention: A Catalyst for Growth?

Experts like Chris Gawne, founder of eurikah, a firm specializing in finding lost pensions, advocate for greater government intervention. Gawne highlights that "Auto-enrolment has turned us into a nation of accidental investors, yet millions of pension savers clearly haven’t been made aware that it’s their responsibility to track what’s happening to their retirement savings." He argues that a consolidated government approach, perhaps by sweeping all relevant data into a single statement and proactively reuniting savers with their pensions, could be transformative. Even at an estimated cost of £16.5 million (for 3.3 million pensions at £5 each), the investment could be quickly recovered through increased tax revenue from the reactivated funds.

The implications for the wider economy are substantial. A £31 billion injection of spending into the economy would undoubtedly have a material impact, stimulating demand and fostering growth. Moreover, shifting this liability from the public purse (as individuals currently relying on pension tax credits might lose eligibility if reunited with their assets) to pension administrators could be cost-neutral for the pension holder and beneficial for government finances.

While a pensions dashboard is reportedly in the works by the Pensions Dashboard Programme, concerns remain about its speed and effectiveness given the fragmented nature of many pension holdings. The existing tracing service's reliance on accurate employer names and pension provider information often renders it ineffective.

The Broader Economic Landscape: Addressing the Aging Workforce

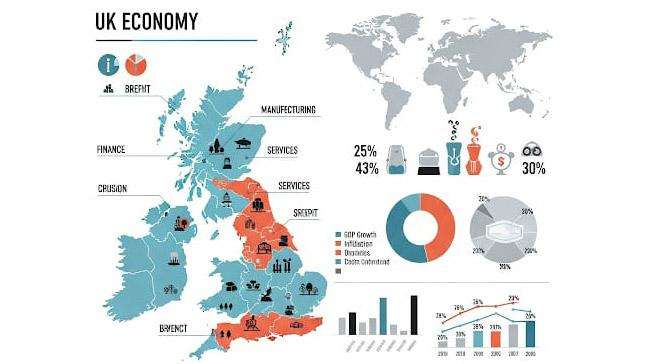

The issue of lost pensions converges with a broader economic challenge for the UK: an aging population and the need to maintain economic growth. The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) recently warned that without a greater share of Britons in their 60s remaining in the workforce, the UK's GDP per capita could grow at just 0.41% annually until 2060, nearly half the rate of the past two decades.

Currently, only 58% of Britons in their 60s are employed. The OECD's Employment Outlook report identified that improving older worker employment could significantly boost the UK's overall employment rate, alongside increased participation from women, disabled people, and migrants. However, the UK faces one of the highest rates of "job strain" among older workers within the OECD, with 15% of those aged 55-64 experiencing stress and demands that outweigh motivating factors, making them less willing to remain in the labour market. The OECD emphasizes that "Improving job quality can be an important aspect to better retention of older workers in the labour market."

Despite these challenges, Britain's old-age dependency ratio (the proportion of over-65s versus the working-age population) is currently in the mid-30s, one of the lowest in the developed world, and is projected to reach 49% by 2060. This relatively strong position has been aided by the influx of working-age Europeans in the early 2000s.

Connecting the Dots for a Robust Future

The twin challenges of unlocking lost pension wealth and ensuring an active, engaged older workforce present both obstacles and opportunities for the UK economy. A government "desperate for growth" should prioritize both. Streamlining the process of reuniting savers with their forgotten pensions, perhaps by collaborating with firms like eurikah, could provide a tangible and immediate boost to the economy. Simultaneously, implementing policies that improve job quality and address job strain for older workers is crucial for long-term sustainable growth. By tackling these interconnected issues, the UK can lay a stronger foundation for a more prosperous future.

_3.jpg)

.svg)