It's doubtful that many UK vice-chancellors have ever heard of Peter Drucker’s seminal book Innovation and Entrepreneurship, let alone read it. Published four decades ago, the book argued that entrepreneurship is not a rare gift but a discipline that every organization can and should practice. At its core was a simple, yet powerful, message: innovation is not optional; it's the essential activity that determines whether institutions thrive or decline.

Nearly forty years later, that warning could have been written for our universities today. Across the UK, higher education is facing a storm of financial and demographic pressures. The Office for Students (OfS) has warned that more than 40% of universities in England are now forecasting deficits for the current academic year, with some in their third consecutive year of losses. This crisis is being driven by a perfect storm of factors:

- Frozen Tuition Fees: Tuition fees for domestic students remain at £9,250, a value that has been steadily eroded by inflation, which has only recently been partially addressed with a slight increase to £9,535 for the 2025-26 academic year. This has left universities with a significant shortfall, estimated by some analyses to be losing approximately £2,500 per domestic student annually.

- Declining International Student Numbers: The financial lifeline of the past decade has frayed. Tighter visa rules, including the ban on postgraduate students bringing dependants, have led to a slump in international student numbers. Institutions with a high reliance on this revenue stream, particularly from countries like India and Nigeria, have been hit particularly hard.

- Rising Costs: At the same time, universities are grappling with soaring costs, including pensions, pay, and energy. A recent increase in Employer National Insurance contributions will further erode university budgets.

This financial instability is not about trimming fat at the edges; it’s a full-blown crisis of survival. In Wales, institutions like Cardiff University have announced significant job cuts, while Bangor University continues to face severe financial difficulties. In England, a quarter of leading universities are slashing staff numbers, with up to 10,000 redundancies or job losses feared across the sector. Universities such as Bradford and Birmingham City have seen widespread strike action in response to cuts. The House of Commons Education Select Committee has even launched an inquiry into university finances and insolvency plans.

The Absence of Entrepreneurship

Drucker might have predicted the response from university leadership: more administration and less entrepreneurship. Instead of embracing change as a source of renewal, institutions are doubling down on cost-cutting, centralization, and control. The qualities Drucker believed defined innovative organizations—clarity, decentralization, customer focus, and systematic entrepreneurship—are glaringly absent.

Drucker insisted that all innovation must begin with the customer. For universities, that means students. Yet, the National Student Survey (NSS) has repeatedly highlighted concerns about value for money, quality of feedback, and employability support, even as the overall student satisfaction trend shows a slight improvement in Scotland following a post-pandemic dip. Instead of redesigning provision around these needs, many universities appear more focused on protecting internal structures and hierarchies.

Drucker also argued that change is the raw material of innovation. Demographic shifts, digital disruption, and global competition should be fertile ground for reinvention. Yet universities too often treat change defensively. The explosion of online learning during the pandemic was largely seen as a temporary solution, not a springboard for more flexible, hybrid, or lifelong learning models.

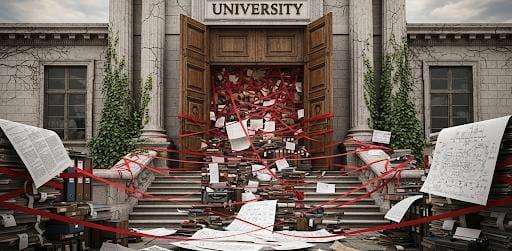

Entrepreneurship thrives on clarity and focus, and yet universities have become masters of complexity. Governance systems are labyrinthine, and managerial bloat has grown even as frontline teaching and research budgets are squeezed. Power has become increasingly concentrated at the center, stripping autonomy from departments and academic staff—the very people best placed to identify and respond to new opportunities. This has created a demoralizing culture of excessive bureaucracy that stifles creativity.

The consequences of these failures are already visible. Financial weakness is forcing job losses, student dissatisfaction is rising, and the UK risks losing not just individual courses but entire institutions, with knock-on effects for local economies and future generations of learners.

This crisis is not inevitable. It is the product of leadership that has chosen to manage decline rather than embrace the entrepreneurial discipline Drucker championed. Politicians also bear blame, having presided over a system that rewards conformity and punishes risk-taking.

The message is clear: universities must put students at the center of everything they do, treat change as an opportunity to reinvent rather than retreat, and embed innovation as a systematic, repeatable process. Unless this mindset changes, the future is bleak. The sector will likely see further job losses, falling student satisfaction, and, ultimately, institutional closures. Drucker warned that organizations that fail to innovate systematically will be left behind. Unless they embrace entrepreneurship as a core management practice, UK universities risk becoming relics of a knowledge economy that has already moved on.

_3.jpg)

_4.jpg)

.svg)

_3.jpg)

_3.jpg)