Just before the 2024 election, two researchers on my team returned from Portsmouth sounding worried. They had been speaking with working-class voters who planned to vote Labour—not out of enthusiasm, but out of a lack of options. These voters were deeply frustrated, desperate for something different, and many said that if Labour leader Keir Starmer didn’t deliver real change quickly, they would turn to Nigel Farage and Reform UK next time.

Back then, the polling was solid for Labour. On the surface, everything seemed fine. But private conversations painted a different picture: Starmer was not inspiring voters. Most were motivated by a desire to get rid of the Conservatives, not because they genuinely believed Labour would transform the country. At the same time, Reform UK was beginning to appeal to many of these voters—not as a government-in-waiting, but as a way to express their frustration with the political establishment.

Now, just weeks before the election, that disillusionment has grown, and the warning signs we saw in 2024 have become much more visible. Reform is now polling in the high 20s, in some cases ahead of Labour and the Conservatives. Starmer’s cautious, technocratic approach has failed to connect with voters who are demanding bold action on the issues that matter most to them: immigration, public services, crime, and the economy.

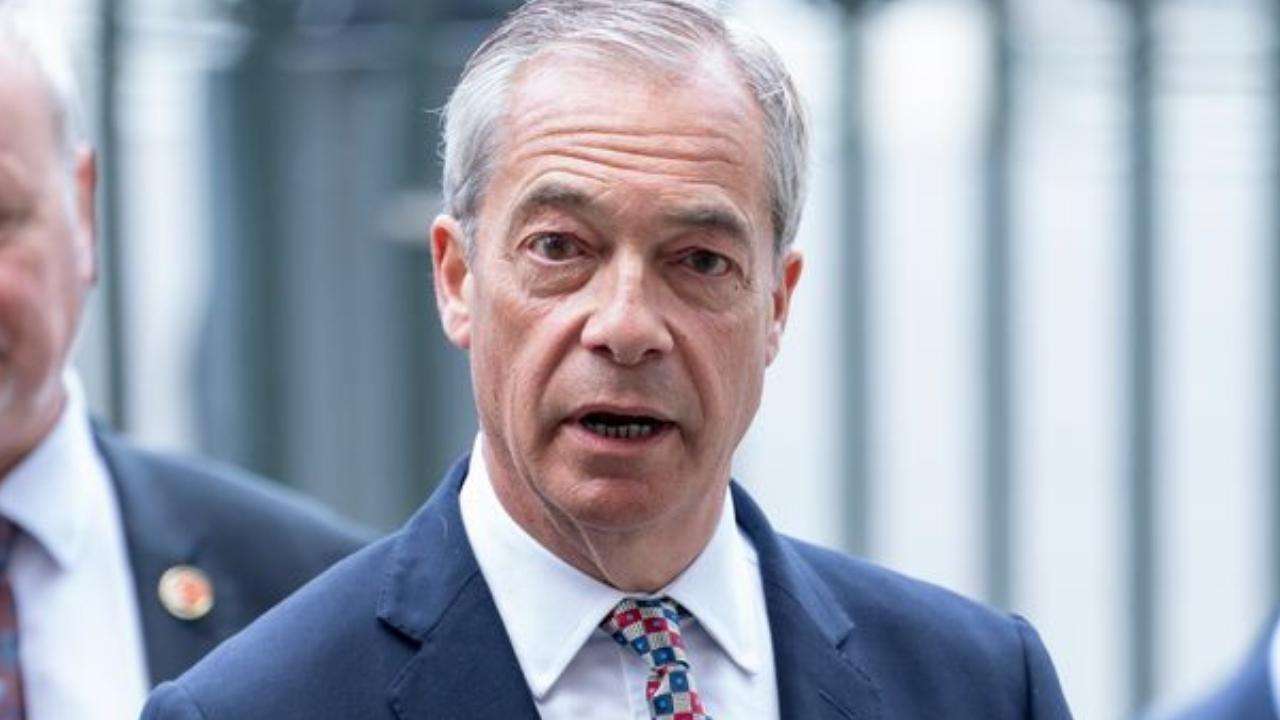

Some polls now even show Nigel Farage ahead of Starmer and Sunak when voters are asked who would make the best prime minister. For a long time, Reform was viewed as a protest party—a way for angry voters to vent without seriously expecting the party to win. But that perception is beginning to shift.

Still, the move from being a protest vehicle to a real contender for power is a massive challenge. Reform’s current coalition—wealthier Thatcherite ex-Tories and lower-income working-class voters—is fragile. These groups often have very different expectations. Farage’s latest set of policies, unveiled last week, showed the difficulty of balancing these conflicting demands.

For example, Reform proposed scrapping the two-child benefit cap and keeping winter fuel payments for all pensioners. These measures were likely intended to soften Reform’s image and broaden its support. But they also opened the party up to questions about how they’d pay for everything, especially when they’re promising tax cuts and shrinking the size of the state.

Farage defended scrapping the benefit cap by linking it to immigration. His argument: if we stop relying on low-skilled migrant labor, we need to encourage British people to have more children. For his critics, this was a thinly veiled form of nativism. But Farage, like Donald Trump, is skilled at walking a line that fires up his supporters while avoiding statements that alienate too many others.

He may even attract some support from certain ethnic minority voters who value British identity, patriotism, and the idea that citizenship should be earned. However, the core of Reform’s rise is not about ethnicity or ideology. It’s about class—and the sense that working-class people have been ignored, condescended to, and left behind.

Farage has long understood the power of this working-class frustration. It helped fuel UKIP’s rise, the Brexit vote, and his own earlier campaigns like the one against the North East Assembly in 2004. At every stage, he and his allies have tapped into a deep sense of betrayal by politicians, particularly over immigration.

When David Cameron promised to reduce net migration to the tens of thousands and failed, working-class voters felt deceived. When Boris Johnson promised the same in 2019 and then saw immigration surge, the anger only deepened. Starmer has not reversed this trend—and, crucially, does not seem interested in doing so. As a result, Farage is now seen by many as the only politician who takes immigration seriously.

This is why Reform is now leading on the issue of immigration. Voters may not believe they can form a government, but they do believe they’re the only ones who care about stopping illegal migration and reducing overall numbers. That belief is powerful—and it’s growing.

So, could Reform actually form a government? That depends on whether their support holds through election day. In 2015, UKIP had a similar surge but won just one seat. Reform will also face huge institutional resistance—from trade unions, civil servants, and the legal system. However, with a smart and disciplined campaign focused on immigration and crime, and careful messaging around the NHS, they could win dozens of seats.

To go further, Reform needs to build a more credible policy platform. Here’s how:

1. Focus on simple, tangible issues that voters care about.

People are tired of potholes, confusing bin schedules, 20mph speed zones, and bad customer service from public agencies. Fixing these issues may seem minor, but they can win real support.

2. Borrow popular policies from the 2019 Conservative manifesto.

Rather than reinvent the wheel, Reform should adopt well-liked ideas on skills training, apprenticeships, education, and transport. These would lend credibility and reduce the need for a massive policy operation.

3. Use expert-led reviews on complex issues like health and social care.

Instead of diving into controversial changes like NHS privatization, Reform could commission serious reviews to explore new solutions while avoiding panic. This would show voters they’re serious without scaring them.

Farage’s past support for an insurance-based NHS system is already being used against him. Reform must emphasize that the NHS will remain publicly owned and free at the point of use. If they don’t, their opponents will weaponize this issue to stop their momentum.

On economic issues, Reform’s best path is a free-market, small-business focus. Many voters feel the system is rigged in favor of big corporations and the public sector elite. By championing small firms and self-employed workers, Reform can appeal across class divides.

In the end, whether or not Reform ever governs is less important than what their rise tells us: British politics is still dominated by anger, disillusionment, and a hunger for change. Labour’s 2024 victory—if it happens—will be built on protest, not hope. And Reform is already preparing to turn that protest into something much bigger.

_3.jpg)

_4.jpg)

.svg)

.jpg)

.jpg)